Arnold Schwarzenegger

The two-grams-per-day maintenance level is the current recommendation by the American College of Sports Medicine’s expert panel on creatine[45]. After using more advanced methods of determining intracellular creatine levels in 2003, however, researchers found that after two weeks of using the standard protocol, intracellular creatine levels returned to baseline[46].

The Keys To Optimal Creatine Dosage and Timing

How do I take my creatine supplement? How much? Do I take it every day? Should I load it initially? Start using creatine the right way!

July 07, 2021 • 5 min read

Sponsored By:

You may think that the majority of research into creatine would be about if it works. But at this point, that’s pretty clear: It does!

For the majority of people, creatine supplements help add muscle mass and strength, improve their training, and help them recover better between training sessions. Next question!

This “next question” is where the confusion usually begins. How should I take creatine for the best results? Is a loading phase necessary? Is it better with carbs or protein? How do I calculate my creatine dosage? The questions go on and on.

If you want to dive deep into the benefits and science, check out the article “Your Complete Guide to Creatine Monohydrate.” But if you’re looking for the quick-and-dirty guide to taking this essential supplement the right way, you’re in the right place. Let’s try and clear up some of the confusion!

Consistency Matters Most!

For every person taking creatine the right way, there are probably two who aren’t. This is unfortunate, because the best ways to take it (and there is more than one way) are all very simple.

“Creatine is not readily assimilated into muscle, as many people would think,” says Darryn Willoughby, Ph.D., in tip 4 from the video “5 Different Ways to Get More from Your Supplements.” “Instead, it takes a while to saturate the muscle.”

For this reason, if you’ve been simply taking a pre-workout that contains creatine monohydrate a few times a week and trusting that it would be enough to help you get huge…it’s probably not. Sorry.

With that in mind, you have two options to get your blood creatine levels up where they need to be: the loading protocol, and the daily low-dose protocol. Here are the pros and cons of each.

Method 1: Creatine Loading

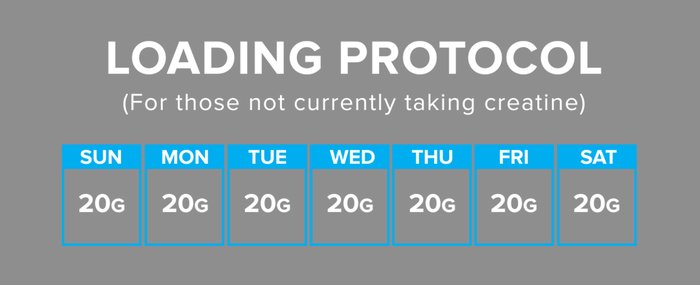

The most common way people will take this supplement is to start off with a “loading phase,” which is designed to fully saturate the muscles’ stores. Then, they move to a “maintenance phase” where they take lower daily doses to keep the levels where they need to be.

Pro: It works! Adam Gonzalez, Ph.D., a supplement researcher and natural bodybuilder, favors the loading approach.

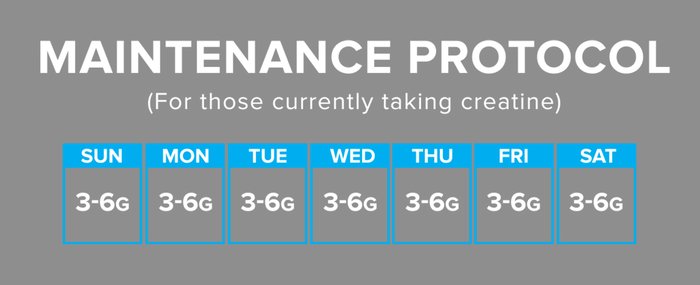

“Research has shown the most effective way to rapidly increase intramuscular creatine concentrations is a loading method,” he explains. “A typical loading protocol consists of consuming high doses, like 20-25 grams per day, split between 4-5 daily doses, for 5-7 days. Following the loading protocol, athletes can generally maintain stores with a daily maintenance dose of 3-5 grams per day.”

Jose Antonio, Ph.D., the co-founder of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, also labels the loading protocol “something you should definitely do” in his video “8 Questions About Creatine Answered.”

Con: Possible side effects. Despite what some gym bros might tell you, creatine will work just fine without a loading protocol. And the standard loading protocol can be a bit unpleasant for some people.

“No, a loading protocol is not necessarily required,” Gonzalez admits. “And the larger daily dosage may cause gastrointestinal discomfort for some athletes.”

If you’re someone who has tried monohydrate in the past but didn’t like the bloating or stomach distress that came with it, then you should definitely try the daily low-dose approach.

Method 2: Low-Dose Daily Supplementation

The alternate method is to simply take 3-5 grams of a creatine supplement each day, without loading. In about three weeks, this approach will get your muscular levels to the same point as a loading protocol.

Pro: It’s simpler, and it still works. “With creatine becoming so popular, many people have ideas about the best way to take it to maximize its effect,” notes Willoughby, whose by-line has been on a number of creatine studies. His advice? “Keep it simple. The most important thing is just to take it daily.”

Willoughby calls taking 3-5 grams daily “the most effective, simple way to supplement.” Over time, that protocol has been shown to produce strength and size gains on par with loading.[1-2]

Con: Possible lower levels, and more time. Research has shown that loading could result in higher overall levels, to the tune of 10-44 percent.[3] So what if you temporarily get a little bloated or have a slight tummy ache? And some research has indicated that the loading phase doesn’t even need to be a week long. It could be as little as 2-3 days and still be effective, as long as you nail the protocol and take 3-5 grams daily afterward.[4-5]

Bodybuilding.com Signature Creatine Monohydrate

Excellent for Muscle Strength, Growth, and Recovery

The Verdict: Should I Load?

Both approaches work, as long as you follow up with a consistent “maintenance dose” of 3-5 grams per day afterward. It’s just a matter of preference, and a willingness to endure some slight discomfort.

When Should I Take Creatine?

You have four options: Before a workout, after, both, or “whenever.” Fitness journalist Adam Bornstein breaks down the options in his article “Before, After, or Whenever: The Best Time to Take Creatine,” but the short answer is that they can all work.

Researchers have looked into the differences between taking creatine at different times, and differences have been minor. For this reason, Bornstein is in the “take it whenever, as long as you take it” camp.

However, other researchers think there may be slight advantages to taking it at specific times. For example, Jim Stoppani, Ph.D., recommends taking it before and after a workout for maximum benefit.

Likewise, Jose Antonio, Ph.D., who co-authored a study on creatine timing in 2013, says there may be a slight advantage to taking it post-workout specifically.

However, Antonio adds that once you have been taking creatine consistently enough to have full reserves in your muscles, it matters far less when you take it. Only if you’re not taking it regularly does there appear to be a difference.

How Do I Take Creatine?

Because it’s tasteless, odorless, and easily dissolves in any fluid, creatine monohydrate is perhaps the easiest supplement to take. Just dump a scoop in water, protein powder, amino acids, or whatever else you drink throughout the day, swish it around, and drink. You won’t notice it at all!

Most scoops are 5 grams, which is a fine dose for athletes of all size. If you’re relatively small or lightweight, you can probably get by with 3 grams, or just over half of a normal scoop.

There is some research showing increased uptake if taken with carbs or protein, but it will work without these additives, as long as you take it consistently.[2] However, if you’re trying to do a brief loading protocol, like 2-3 days instead of the normal 5-7, taking it with carbs is probably a good idea.

One study showed that taking around 100 grams of carbs with 5 grams of creatine increased total muscle creatine by 60 percent.[5] Another showed similar results by taking 5 grams with around 50 grams of carbs, and 50 grams of protein—the equivalent of two scoops of protein and two bananas, a cup of grape juice, or a cup of cooked rice.

What if I Miss a Day?

Once you’ve achieved saturation, either by a loading protocol or consistent low-dose supplementation, don’t sweat it if you miss a day or two. Your levels can stay elevated for as long as 4-6 weeks.[6,7]

After that, just keep taking it, and keep enjoying better workouts and results!

References

- Willoughby, D. S., & Rosene, J. (2001). Effects of oral creatine and resistance training on myosin heavy chain expression. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(10), 1674-1681.

- Willoughby, D. S., & Rosene, J. M. (2003). Effects of oral creatine and resistance training on myogenic regulatory factor expression. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(6), 923-929.

- Greenhaff, P. L. (2001, September). Muscle creatine loading in humans: Procedures and functional and metabolic effects. In 6th Internationl Conference on Guanidino Compounds in Biology and Medicine. Cincinatti, OH.

- Steenge, G. R., Simpson, E. J., & Greenhaff, P. L. (2000). Protein-and carbohydrate-induced augmentation of whole body creatine retention in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology, 89(3), 1165-1171.

- Green, A. L., Hultman, E., Macdonald, I. A., Sewell, D. A., & Greenhaff, P. L. (1996). Carbohydrate ingestion augments skeletal muscle creatine accumulation during creatine supplementation in humans. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism, 271(5), E821-E826.

- Vandenberghe, K., Goris, M., Van Hecke, P., Van Leemputte, M., Vangerven, L., & Hespel, P. (1997). Long-term creatine intake is beneficial to muscle performance during resistance training. Journal of Applied Physiology, 83(6), 2055-2063.

- Candow, D. G., Chilibeck, P. D., Chad, K. E., Chrusch, M. J., Davison, K. S., & Burke, D. G. (2004). Effect of ceasing creatine supplementation while maintaining resistance training in older men. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 12(3), 219-231.

About the Author

Shannon Clark

Shannon Clark is a freelance health and fitness writer located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Creatine is the most scientifically significant supplement of the past thirty years, and I’m not just talking about the bro-science here. It’s obviously known for making athletes bigger and stronger, but that’s not all it has to offer. Creatine’s benefits are numerous, but what most people—including most supplement manufacturers, if labels are any indication—don’t understand is what it does at the cellular level. This is important because your creatine levels can affect nearly every cell in your body.

Believe it or not, we’ve known about creatine for over a century[1], and we’ve known for nearly that long that supplementing with it does good things. For years now, the basic explanation behind creatine’s efficacy is that it’s the active transport of ADP (adenosine di-phosphate) back into ATP (adenosine tri-phosphate). An elegant explanation, to be sure, but what does it actually mean?

Beyond the Bro-Science

ATP is the energy currency of your cells, and ADP results from the breakdown of ATP, which releases a phosphate molecule and ADP. ADP is then recycled, a phosphate is reattached, and ATP is formed again. Each of your cells contain mitochondria, which convert fatty-acids, ketones, and glucose into ATP via the Krebs (or citric acid) cycle.

At rest, mitochondria don’t emit ATP or absorb ADP—which can be recycled into ATP in mitochondria[2-5]. Creatine instead interacts with an enzyme system called creatine kinase (CK) that’s located on the outer surface of mitochondria. It then picks up a phosphate molecule from ATP in the mitochondria, turning the ATP into ADP[6-10]. Once the creatine grabs a phosphate, it’s then called creatine phosphate.

Creatine phosphate then delivers the phosphate to the area of the cell that does work, where creatine kinase removes the phosphate from creatine phosphate and combines it with ADP at the source of the work, converting the ADP back into ATP. Creatine transports the energy produced by mitochondria directly to the working parts without invoking a long series of chemical steps. It’s a brilliant system.

Creatine is the material that keeps all of our cells supplied with energy through a very efficient mechanism, keeping intracellular ADP levels very low. This is important because as this concentration increases, cellular respiration decreases and can trigger the need for fast energy[11-14]. By keeping ADP levels low and recycling ADP back into ATP at the site of work, you can produce peak power for a longer period of time.

Energy Systems

Cells have three energy systems—one aerobic, and two anaerobic. One of the anaerobic systems, the glycolytic, is where glucose is burned to produce ATP. The other, the ATP-CP system[15-18], actually kicks in before the glycolytic cycle. When power production ramps up quickly, your cells need ATP at a rate higher than free creatine can supply by grabbing a phosphate molecule and delivering it to the myofibril to get turned into ATP and then burned.

When you begin intense activity from rest, you already have a huge store of ATP and creatine phosphate. Your cells burn through the ATP stores, and creatine phosphate recycles ADP into ATP, but CP becomes exhausted in the process. Within cells, ATP levels never fully deplete, even at fatigue. Creatine phosphate levels, in contrast, can become almost totally exhausted[19-20].

Your ATP-CP is essentially like a battery. Your cells build up a surplus of CP and ATP during rest—and you can tap into this surplus for rapid energy. Burning up the CP prevents the buildup of ADP, which can decrease energy production when levels get too high. Supplementing with creatine can increase CP levels by up to 20 percent[21-23], giving you a bigger battery when you need it.

This battery acts fast, though, lasting only long enough for the glycolytic cycle to ramp up. This cycle then only lasts long enough for the oxidative system to ramp up. These three systems don’t operate in isolation—they definitely overlap—but they each have a period where they produce the majority of the energy for the entire system.

ATP-CP is critical for resistance training, sprinting, and HIIT because of the relatively sort timeframe during which it acts. Creatine supplementation does almost nothing to enhance endurance in performance[24-28], but even relatively short exposure to supplementation can improve sprint and power performance[29-37].

It’s been shown by research that training may not be able to do anything to specifically alter the ATP-PC system in isolation, because it’s always tied with the peak output and timing of the glycolytic cycle[38-40], acting only to bridge the first five seconds of high-output performance. Supplementation, however, seems to have the ability to help here.

Many Varieties, One Choice

There are several different types of creatine supplements on the market. I won’t go over all of these in any detail, because it’s possible to create your own creatine “salts,” but also because it’s kind of pointless. No other version has been tested to the degree of creatine monohydrate (CM), and no other creatine spinoff has proven to be nearly as effective. I could explain this further, but I don’t want to irritate any supplement manufacturers here by explaining the science behind why their claims aren’t valid.

Creatine monohydrate is incredibly well-studied—and nearly every study referenced in this article utilized CM. It’s one of the most stable forms of creatine in solution, it’s not degraded during normal digestion, and 99 percent is either absorbed by muscle tissue or excreted through sweat or urine[41-42]. Other forms of creatine may be more soluble, but that has nothing to do with effectiveness. Creatine monohydrate is simply your best—and cheapest—choice.

The Dosing Rationale

Researchers initially found that 20 grams per day of creatine, taken for five days, successfully raised muscle creatine content by 30-45 percent. The same protocol—20 grams per day, then maintenance of supraphysiological concentration with 2-3 grams daily after that—has been used since 1996[43] with little to no deviation in the research.

Consider the fact that a 150 pound male (70 kilograms) will burn through about two grams of creatine naturally every day[44]. Since 95 percent of creatine exists within muscle tissue, the average resistance-trained athlete would require greater amounts of creatine just to maintain normal cellular levels.

The two-grams-per-day maintenance level is the current recommendation by the American College of Sports Medicine’s expert panel on creatine[45]. After using more advanced methods of determining intracellular creatine levels in 2003, however, researchers found that after two weeks of using the standard protocol, intracellular creatine levels returned to baseline[46].

The 20 grams-per-day mark was little more than an arbitrary choice by early investigators, and for some reason, it stuck. Even researchers using formulas accounting for bodyweight and body mass still assumed that a 150 pound man should take 20 grams of creatine per day. Nobody tested this assumption.

This can’t possibly be the optimal dosing schedule for everyone. Humans carry about two grams of creatine per kilogram of lean muscle mass (one gram per pound). The maximum we can put into muscles is about 3g/kg (1.4g/lb)[47]. To hit this level, a 150 pound male would need about 25 grams of creatine supplementation.

To increase the amount of creatine we carry to a level above the baseline (1g/lb), we need at least two grams per day for maintenance, plus 0.4g for every lean pound of muscle. For a 200 pound male carrying 60 pounds of lean muscle, a reasonable calculation would be:

(0.4g/lb * 60 lbs)/0.95 + 2g ≈ 27.3g

My hypothesis is that this would be the minimum amount of creatine needed, daily, to maintain maximum intracellular levels—with the division by 0.95 taking into account the amount of creatine absorbed by the rest of the tissue in the body. There may be a better way to estimate the minimum daily dose, but the data for this doesn’t yet exist.

This alleviates the need for a loading period. If you’re fairly lean, this leads to a simple formula:

- POUNDS: Bodyweight * 0.15 = grams of creatine monohydrate to ingest

- KILOGRAMS: Body mass * 0.3 = grams of creatine monohydrate to ingest

Although these formulas would appear to overestimate needs, bear in mind that one gram of creatine monohydrate is only 88 percent creatine. The overage takes this into account.

Dosing Considerations

Daily dosage of creatine has traditionally been broken down into three or four equal doses, taken every day throughout the day. Again, this has never been directly tested to see whether it’s necessary. In fact, one group of researchers may have proven that you don’t need to take creatine all day—and that you don’t need to take it every day—as long as you’re averaging the necessary amount per day[59]. Instead of taking 30 grams per day, it may be possible to take 60 grams every other day for the same results. This leads me to believe that taking creatine in divided doses all day long is probably unnecessary.

How should you plan your timing, then? Well, ingesting creatine with large amounts of carbohydrates can actually increase retention of creatine within muscles[49-52]. Although there hasn’t yet been heavy research on this, it’s believed to have something to do with an interaction with insulin[52].

Although I think researchers are on the right track here, I actually think it has more to do with an interaction with GLUT4, which I’ll get to in a moment. Suffice it to say, for now, that with Carb Back-Loading, the best time to ingest creatine would be immediately post-training, with carbs. You can divide this dose, but if you’re using creatine monohydrate, it’s also possible that one large load can do the job.

Avoid taking creatine with caffeine, because in the absence of carbs, it can actually prevent a rise in intracellular creatine levels[53-54]. Again, this may have something to do with GLUT4 transporters, since caffeine can prevent GLUT4 activation. Anything that increases GLUT4 content and translocation (carbs and resistance training) will improve the results of supplementation, and anything that doesn’t (caffeine and endurance training) will negate the effects.

Don’t take creatine with coffee. Do take it with training and/or carbs. Otherwise, take it however you’d like. Just make sure you take enough.

If you’d like to see Kiefer’s sources, click here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR